Outside the box: how Nigeria won the fight against polio

Nigeria is now free of wild polio. On 21 June 2020, the African Regional Certification Commission, an independent advisory body of the World Health Organisation, certified that the country eradicated the disease.

The victory was hard-fought. For decades, health officials encountered numerous challenges to eradication, despite understanding the roots of the disease and receiving the necessary resources from the international community to fight it. By the end of 2010, it seemed that the country was finally on the verge of winning the battle—that year, there had been only 21 recorded cases in the whole country—but spikes in cases over the next two years (62 in 2011 and 99 in 2012) signaled there was more work to be done.

Health officials were puzzled by the spike; they had reached vaccination rates above 90 percent for children under the age of five, the threshold required to eliminate the disease. Initially, officials suspected that vaccination delivery campaigns struggled because of challenges arising from conflict and negative perceptions of foreign medicine; these suspicions seemed to be supported by the fact that most of the new outbreaks were in the north, where conflict and negative perceptions are more common. But then Yau Barau, who in his work with the National Primary Health Care Development Agency (NPHCDA) has been on the frontlines of this battle for over a decade, realised that they needed to think outside the box. Soon, Barau and his colleagues saw the real root of the problem was that the vaccination teams were using faulty maps.

While driving through Gangara Ward in Katsina State during a vaccination campaign, NPHCDA officials and local teams noticed an inconsistency: the number and location of settlements on the hand-drawn maps at the ward headquarters did not match what they were seeing on the ground. To get a more systematic understanding, they visited a sample of 25 settlements that appeared on these hand-drawn maps, collected names and geo-coordinates, and overlaid them with satellite imagery from Google Earth. The maps were indeed faulty; numerous settlements were not correctly located or named, and some settlements were missing entirely.

Gangara Ward, Jibia Local Government Area, Katsina State

Hand-drawn map (left) and improved digital map (right)

Applying the same methodology to other regions of the country, they found that the areas in the north where outbreaks were occuring all had faulty maps. In response, experts worked with local communities to develop a comprehensive methodology for generating validated digital maps. Community buy-in around the methodology ensured trust, which in turn allowed for accurate data collection at the local level. Local cartographers were trained to collect boundary information for wards (the smallest administrative division in Nigeria) and the names and coordinates for every settlement in each ward. The improvements in the local maps were remarkable. Settlements of up to 1,000 people that had previously been unmapped and had not been visited by vaccination teams in many years were now precisely located and named.

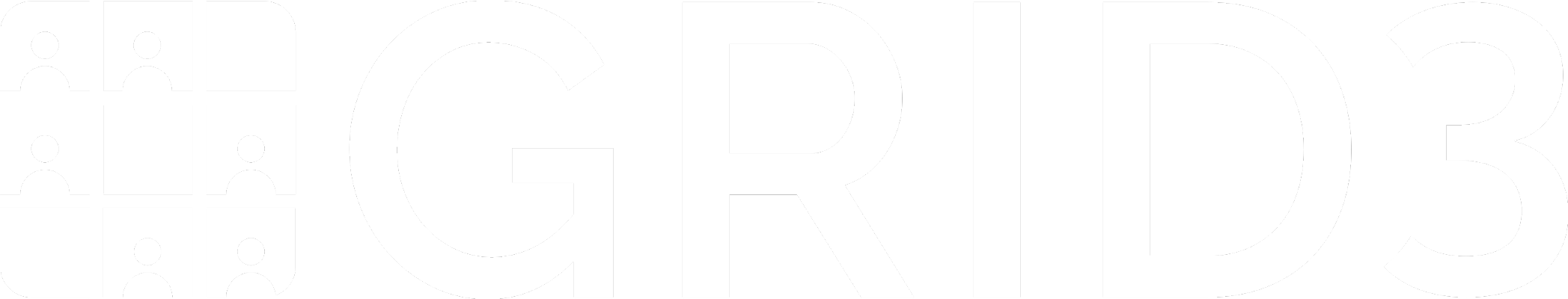

With support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the NPHCDA mapped 10 northern states over two years. By incorporating high-resolution satellite imagery, machine learning, and advanced data science methods, these maps were able to include comprehensive delineations of each settlement and spatially precise population estimates (these additions were made possible through a partnership with Oak Ridge National Laboratory and WorldPop/Flowminder). The enhanced maps could now not only ensure that each settlement was included in vaccination plans, but also enabled significant improvements in plan efficiency. Equipped with spatially precise, accurate data, planners could better allocate vaccine supplies and better design vaccinator travel routes.

This map shows population estimates, per 90m x 90m grid square, for a region in Kano State. Such estimates were aggregated to settlement and ward levels so that vaccination teams could create accurate plans.

“Integrating geospatial data into our vaccination planning processes was the number one game changer,” says Barau. “Seeing the joy and happiness of our vaccinations teams confirming that the hamlets or settlements were at the right place, with the right name, was a turning point in our fight against polio. When communities validated our data and we started using [the data] for implementation, we felt we were really going somewhere. Teams worked long hours to finish their work, as we knew that we could eradicate the disease if each vaccination team met 100% of their objectives. This approach enabled that.”

Outbreaks fell to zero and have stayed there. These innovations did more than help eradicate polio in northern Nigeria; they led the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the United Kingdom’s Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office to create GRID3 so that the mapping interventions could be scaled up to all of Nigeria and extended to other countries.

“The fight against poliovirus in Nigeria and the final declaration of Nigeria as free of wild polio was made possible through the utilisation of geospatial technology,” says Dr. Faisal Shuaib, Executive Director and Chief Executive Officer of NPHCDA. “GIS-based maps from the GRID3 Nigeria data improved the micro-planning process, thereby enhancing the ability of frontline healthcare workers to accurately identify settlements and track under-five children to be immunised with polio vaccines.”

“The job of eradicating polio began in 1955 with the development of the first vaccine. The task of finishing that job lies with organisations like NPHCDA, whose discovery of the power of geospatial data is in some ways as momentous as what happened in 1955. We’re proud to continue working with NPHCDA,” says Marc Levy, the Director of GRID3.